In the late summer and fall the shoreline around the East End is abundant with Stripped Bass and Bluefish. Surf casting is as easy as throwing out a line. If I was fishing at Town Line Road it was no fluke to reel in two fish on one lure. The first sign of a school are seagulls working the water’s surface. They’re dipping down to pick up scraps churned up by the feeding frenzy going on just below the surface. A school can move closer to shore, running the baitfish in that are literally jumping onto the beach to escape. You can see the Blues right in front of you. Or the school will run up and down the beach chasing the bait. Sometimes they swim by but if you have four wheel drive you can move up the beach, get ahead of them and wait. At times I’ve seen fish in massive schools like the shadow of dark clouds over the water running up and down the beach as far as you could see. In Montauk I’ve seen them fill an entire cove hundreds of yards across. It’s something like a scene from a wild nature show. Even if you’re not an avid fisherman with all the gear it’s exciting to watch and the action can make even for a novice an easy and delicious dinner. There’s nothing like a fresh striper or a blue you’ve caught at 6:00, filleted and on the grill by 7:00.

Private Collection, circa 1960’s

The local Baymen of the East End go as far back as the early settlers here. As my friend Peter Maas put it, “when men put to sea in their with their seine net to maintain themselves, a time now destroyed by huge offshore fishing fleets, by pollution, by the crunch of the late 20th century”. Soon after I moved out here one of the first events that had an influence on my work happened on the beach in Amagansett. The Baymen had formed their own association to band together in order to preserve their vanishing way of life. Offshore commercial fishing boats were in the early stages of overfishing the waters. The commercial fishing lobby helped set into motion state laws that inhibited the way the Baymen had fished for decades. Many couldn’t make a living anymore and gave up. In 1990 the Dept. of Environmental Conservation (DEC) banned haulseining. An event was staged in protest in Amagansett. They would demonstrate one last time how is was to catch fish even though they risked going to jail for doing so. Well over a hundred people showed up in support. I did too and to watch these men launch their dories into the surf to catch fish in the same way they had done since the area was settled. It was important to watch them aim their dories for the surf and drive them into the water by a pickup truck in reverse and then row out and down the beach dropping a long net until they would turn the dory back to the beach, then winch their nets in from the bed of another truck, hauling ashore a variety of fish, the most valuable being the American shad, weakfish, bluefish and striped bass, that were caught in the drag net. This time has been sadly lost and well documented in Peter Matheson’s book “Men’s Lives”. I’m sure I witnessed the last of these great catches. A great place to visit in the summer is the East Hampton Marine Museum in Amagansett. There is an amazing collection of photos that document the last years of the Baymen. There’s a great steel dory, it’s hull painted with the stars and stripes out front and some interesting artifacts from the East End in the three floors of this old shingled building that houses the museum. The Baymen’s Association used to hold their quarterly meetings there. I joined and was a member in good standing for a few years, meaning I gave $100 annually in contribution. These men didn’t know me from any other outsider but were always polite and friendly. In 2005 there were only 17 members left and they sadly disbanded. Today a new boat shop adjoins the museum which houses the East End Classic Boat Society. Their mission is to maintain and advance traditions of classic boat design, construction, maintenance, and seamanship through education, demonstrations, and sharing resources and ideas.

The dory purposely entered into my work as a symbol of that bygone era. It’s important to remember because without memory we are lost to forget where we came from. Overturned, used, forgotten. The symbol of the dory took on that meaning. One of the first pieces I did concerning this thought was this small impression, almost abstract image and rough in the handling of paint, titled “Inward bound”. The essence was what mattered most. My work was changing from abstract to representational at the time. It was my first crude attempt at putting this shape onto canvas.

Inward bound, oil on canvas, 1989, 17″x25, collection of the artist

I imagined that larger version titled “Alone, Adrift” that depicted the dory, floating in tis own space. gain the surface was heavily handled with brush strokes, drips and pouring of the paint. It seemed to represent a lifting of the spirit, an inanimate object that had some etherial life of its own. It’s hangs upstairs on a side wall in a room with a 20′ vaulted ceiling, appropriately above an old church pew as if there was some relationship to the stations of the cross.

Alone, Adrift, oil on canvas, 80″x100″, 1989

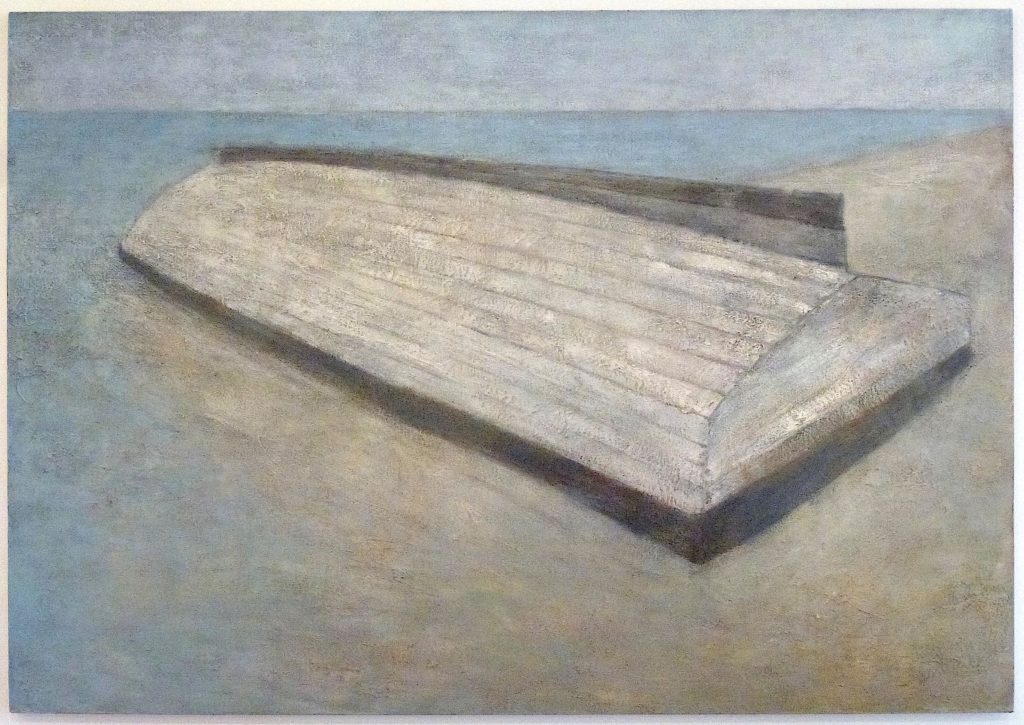

The next large piece seems to be more grounded, an overturned boat with a lapstrake hull. It supposed to be on a beach. There’s an obvious horizon and shoreline in the upper right part of the painting but in the lower left side it disappears and becomes more of a reflection, to me a metaphor of looking at the past.

Overturned Dory, oil on canvas, 70″x100″, 1990

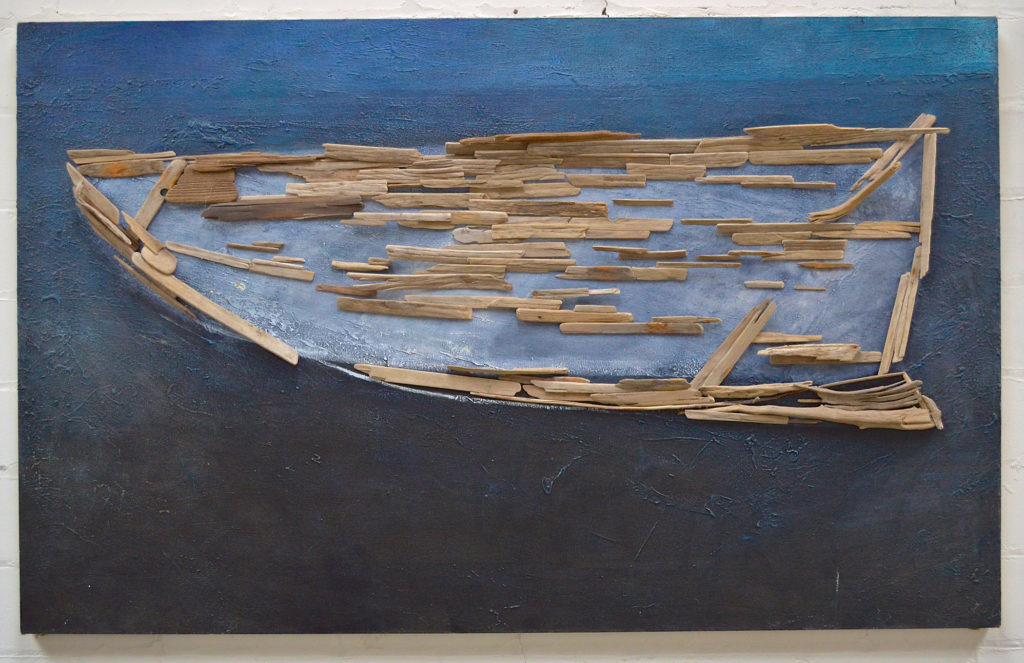

Over the years I’ve continued to return to this image. When I’m bored or tired of doing landscapes I intentionally switch off that part of my thinking and work on something different. I started doing these driftwood pieces three or four summers ago to get away from landscape painting. As much as I enjoy that, it becomes more labor than love. The “Driftwood Dory” happened by forced accident. I pulled an old painting out of the rack that I never quite resolved and decided to rework it, painting over and applying driftwood to the surface. Every afternoon that summer I’d take a break in the afternoon and spend an hour collecting pieces of driftwood on the beach. The pieces on this painting in particular are broken pieces of dune fencing that is staked along the dunes in the winter to help prevent erosion. This only partially serves its purpose. The Nor’easters of winter wreak destruction to the coastline here as 50-75 mph winds wash the surf up to the dunes and rakes the dune fencing away. The fence, after several months of being tumbled down the beach ends up in small pieces left to dry out in the hot sun of summer. They’re slightly curved and twisted into the shape of a single steamed lapstrake piece that gets wrapped to a the ribs or vertical frame of a wooden hull. The most significant part of this whole process to me was that I had no idea what I was doing. I’d never done anything like it. I was putting together parts of a puzzle without a picture to go by. Still, they made sense somehow. tbc…

Driftwood Dory, oil on canvas with driftwood, 55″x88″